February 23, 2021

The Power of Listening to Patients: Living With Undiagnosed Autism

In December of 2019, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) updated their guidelines for the diagnosis of autism for the first time in over a decade. Less than thirty years ago, research showed the prevalence of autism could be as little as 1 in 2,500. Now, experts rate it closer to 1 in 54.

The question is, is the large uptick in cases due to more autism? Not exactly. There is now simply a better understanding of what ASD presents as.

That’s why the leading professional association of pediatricians now recommends children be regularly screened for autism as young as nine months old (and then again at 18, 24, and 48 months).

In some parts of the U.S., this aggressive approach is making a difference. In New Jersey, 1 in 32 (3.12%) children are currently diagnosed with ASD. But the truth is, diagnosis rates vary from state to state, with rates as high as 4.88% in Florida to as low as 1.54% in Texas.

What’s happening to those children in low diagnosed areas? They’re likely being missed.

When the Signs Are There

Alice Marrakesh was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at 26 years old.

As early as elementary school, Alice struggled to keep up with her peers. She recalls spending an excessive amount of energy trying to look like other girls and parrot the way they spoke, all while keeping up with her schoolwork. Despite her best efforts, she felt she couldn’t connect with other girls on the playground, have close friends, or make a positive impression on her teachers.

“Teachers were always saying ‘She’s really smart, but she daydreams,’” or, ‘she needs to speak up more in class,’” Alice reflects. “One time, someone said, ‘She’s missing the easy questions; she just really needs to pay attention,’ but I didn’t know how.”

By the time Alice got to high school, her social circle was small, and her stress levels were becoming more significant. As the work got more challenging, she developed anxiety, depression, gastrointestinal issues, and even suffered from heartburn in her attempts to get straight A’s.

“Nobody ever said, ‘Hey, does your child have anxiety, could she be anxious? Maybe we can help her with that.’ They were just like, ‘Here’s an inhaler.’ I remember blowing on the thing that measures your lung capacity, and it was at 100, and I still couldn’t breathe, and nobody would help us. That was the extent of any help the doctors ever gave us.”

Growing Up Different

Alice was born in 1990, a time when “autism” was hardly a spoken word, much less a common diagnosis. Add to the fact that Alice was a girl who, even today, are disproportionately diagnosed.

Unfortunately, stories like Alice aren’t rare. Over the past few years, an increasing number of adults have received an autism diagnosis, sometimes due to their child being diagnosed or from merely reading other autistic people’s stories and seeing similarities in their own.

“My whole life, I thought there was something wrong with me. My diagnosis changed those thoughts. When I learned about my diagnosis, I knew nothing was wrong with me…I knew that I had something very special about me and my life was about to change,” Samantha Ranaghan wrote, after being diagnosed as autistic at age 34.

“Finally, I had a name for the thing that had made me feel like an alien for so long. Finally, I could stop feeling bad about being different,” Barney Angliss shared after receiving his diagnosis at age 40.

For many adults, it isn’t about blaming their shortcomings on a diagnosis; it’s just a new tool for understanding themselves and how their brain works. In Alice’s case, getting a diagnosis gave her the power to step back and think, ‘Okay, I’d like to learn these skills,’ rather than entirely falling apart when faced with everyday tasks, like making her bed.

For the first 26 years of her life, Alice didn’t have that luxury. Instead, adults in her life repeatedly reprimanded her for not trying harder, often saying things like, ‘You know what you need to do, you just need to do it.’

“And I thought, either I can’t do what I need, or I just don’t know how,” Alice admits.

Before long, Alice had developed masking skills—which she still believes are necessary to survive in society. She left her home in Philadelphia for brighter pastures, attending college in California. She joined her peers at parties, started binge drinking, switched her major a couple times, and by the end of her first year at school, was slipping into a deep depression.

“I remember looking around and saw all the kids on the grass, talking and laughing and walking around with their backpacks and doing their clubs. It felt like I was on a different plane looking through a glass. I just remember thinking, ‘I don’t think this is normal.’”

Alice sought guidance at the campus counseling center and soon after received prescribed medication, which she explained made her feel worse. Soon, she was sleeping all day, having full-blown panic attacks, and trying to convince her psychiatrist that she had Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD). In response, he gave her a list of breathing techniques.

By her third year of college, Alice learned her campus had disability support services, which she credits to helping her get an ADD diagnosis, but thought at that point it was too late. Now, she was struggling with a substance use disorder, had cut her schedule to one or two classes, and was unable to get out of bed regularly. Before she could graduate, her parents insisted she return home to Philadelphia.

“When I came home, it just got worse and worse. I just went into depression completely. That lasted for like seven years. I was just seeing one professional after another, after another, after another. Over the years, I probably saw 15 professionals. Honestly, that might be an underestimation,” she recalls.

Easing the Transition to Adulthood

When Dr. Susan Levy and her colleagues set out to update the AAP’s autism guidelines, they realized a key focus shouldn’t be just early childhood; it had to include the transition to adulthood.

Dr. Levy noted that while the past twenty years of autism research had been heavily focused on identifying the developmental disorder and the causes behind it, something important started to happen. The children were growing up.

Now, thousands of undiagnosed children like Alice were entering their adulthood without the tools they needed to survive: whether that be therapy, medication, support services at work or school, or even just validation.

Furthermore, nearly three-quarters of children with ASD have comorbid conditions. A Swedish study published in 2019 found autistic adults more than twice as likely to die prematurely than those in the general population. The causes were most commonly linked to circulatory disorders, neurological disorders, cancer, and suicide.

By better identifying comorbid conditions, medical professionals can better prepare patients with autism for every transition in their life.

Alice’s comorbid conditions included gastrointestinal issues, anxiety, depression, ADD, and substance abuse disorder. After returning home, her parents sought professional help for her, insisting that something out of the ordinary was going on with their child. No matter who Alice talked to, she never heard a diagnosis outside of severe depression, anxiety, or ADD.

In the midst of their search for answers, Alice got more frustrated. She felt like she was being dismissed at every turn. Finally, Alice decided that if she was going to get answers, she would have to find them herself.

The first time she considered potentially having autism was after taking an online quiz.

“I was like, I really identify with a lot of these things, but obviously I’m just being a hypochondriac or something,” she remembers. “I never saw any presentation of anyone like me. And I had felt like the whole system had been extremely invalidating. I would tell them something, and they would say to me, ‘Your thoughts are distorted, your thinking is distorted, your problems stem from the fact that you’re too anxious, or you’re too depressed, or you’re being too negative. You just need to change your thoughts and be more positive and try harder.’”

As a result, she dismissed autism altogether. Then, she had her worst therapist interaction to date.

“First, he told me I was the most depressed person he’d ever seen in his life. I was telling him, ‘Listen, I’m trying to do things to get out, but when I try to drive here, I can’t find it—every single time. I’ve been here like 15 times, and I get lost here every time, it’s really stressful, and I can’t handle it. It’s so upsetting. I think there’s a cognitive issue going on here. He thought I was so depressed that I was distorting reality to the point where I couldn’t do things when I could.”

At one appointment, Alice’s therapist pointed to her transcripts, showing good grades earlier in life to prove she didn’t have any cognitive differences. Alice faced a recurring theme of she was doing really well until a certain point, and now she’s depressed.

When Alice insisted, her therapist responded, ‘You don’t strike me as any of those [autistic] guys that I’ve seen.’”

He wasn’t wrong. Alice could make eye contact and carry a conversation, two notable signs of autism thought to be required for a diagnosis in the early 2000s. But she couldn’t find a way to function. His diagnosis? A case of psychosis caused by depression.

The Importance of Listening

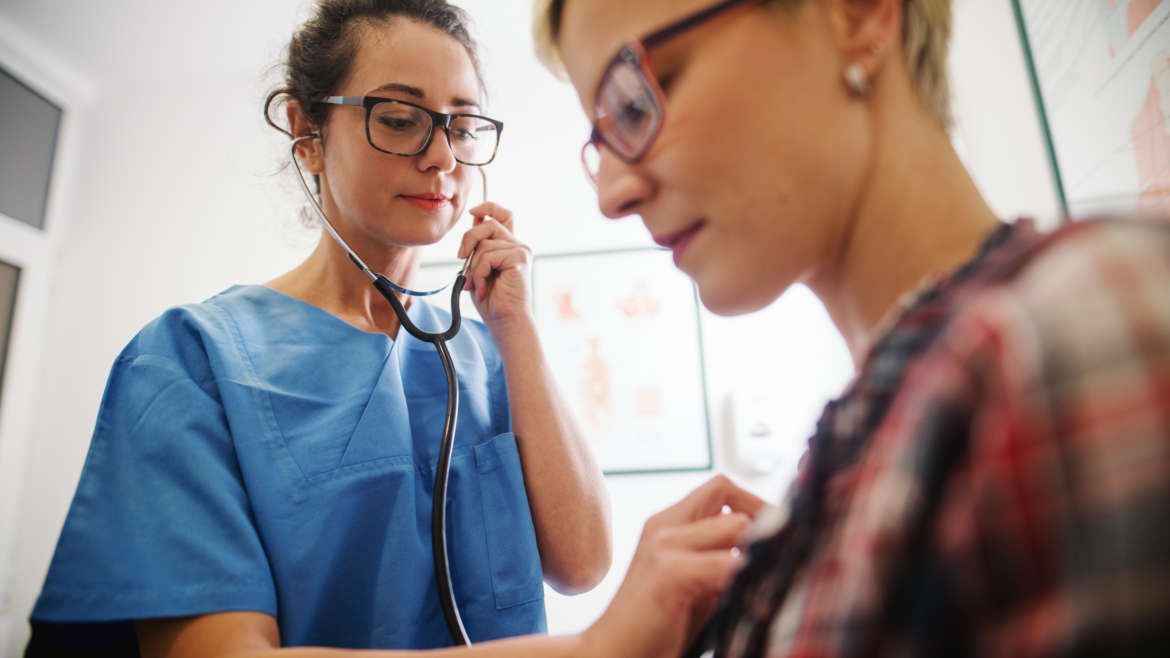

It’s no question that every patient deserves to be heard—but what are healthcare professionals supposed to do when the patient has troubles communicating?

While not every autistic person has communication challenges, for those who do, expressing their medical concerns can make the difference between life or death. There are reported cases, for example, of appendicitis being mistaken for stomach pains. Or a misunderstanding in pain perception to result in delayed diagnosis. It begs the question, is the healthcare system taking care of autistic patients sufficiently?

In a 2013 study, researchers found autistic adults reported “lower satisfaction with patient-provider communication, general healthcare self-efficacy, and chronic condition self-efficacy, higher odds of unmet healthcare needs related to physical health, mental health, and prescription medications, and greater odds of using the emergency department.”

Ultimately, HCP’s need to find a way to grow with their patients to ensure everyone is receiving the same level of care. For Alice, that starts with listening to, hearing, and believing your patients.

The turning point came for Alice when she connected with a therapist who validated her experiences and truly listened to her. She met with a psychiatrist who believed in treating her concerns symptom-by-symptom, which helped ease her depression and anxiety. And a caseworker she didn’t know she was entitled to unexpectedly showed up at her door one day, asking if she’d ever thought about getting an autism diagnosis.

“Yes!” Alice exclaimed.

In no time, the caseworker connected Alice with a free study being run by Brenna Maddox, Ph.D. After seeing over 15 health professionals, overcoming a substance abuse disorder, being prescribed medications that left her bedridden, and feeling incapable of fully functioning for 26 years, Alice finally got the answer she had felt deep down all along. Dr. Maddox diagnosed her with autism spectrum disorder.

“I was so relieved. I was really, really happy. I think I started being strong in this belief when I found an article on Spectrum News about The Lost Girls.

“I remember printing this article out and giving it to my psychiatrist. I think she was supportive of me getting the test, but even just something like that article can really change someone’s life. I carried that thing around with me to a couple of different providers just to make sure they knew I wasn’t making this up.”

Although getting the diagnosis didn’t instantly solve all of Alice’s problems, she felt like she was finally headed in the right direction. Her therapy sessions were helping, her psychiatrist was appropriately able to treat her symptoms, and her depression turned around as a result.

“I went from feeling like there was this whole world that I could barely make it in, I couldn’t function in: feeling like I’m a failure at everything and I don’t know why and they tell me that I’m smart, but I can’t do it, and what’s the point of living. And then just turning the whole thing around. I’m not a failure. I’m a pretty successfully functioning person in the neurodivergent community. It just took the whole guilt and blame off of me.”

Now, Alice has been sober for seven years and serves as a peer specialist in mental health and autism. She was able to return to school and will be graduating with a Behavioral Health Counseling degree this year. She is an advocate for other autistic people like herself and is working on overcoming her depression and anxiety with a team of professionals she completely trusts.

When asked how healthcare professionals can learn from her experience, Alice believes it just comes down to listening.

“Believe people. Believe them when they tell you of their feelings and their stories and their experiences. Do that before trying to diagnose, fix, or change anything. Just take the time to listen and really understand their mind.”

ECHO Autism is a community of autism experts dedicated to bringing high-quality specialty care to local communities through telehealth. Through guidance, knowledge, and training, ECHO Autism is helping providers all over the world learn more about autism spectrum disorder by connecting specialist teams with local care to benefit and empower autistic people and their advocates.

ECHO Autism partnered with Autism Speaks to offer a wide variety of free, evidence-based resources that can be shared with patients to help them navigate an autism diagnosis. This includes the “100 Day Kit for Newly Diagnosed Families,” “First Concern to Action Tool Kit,” and the “Transition to Adulthood Tool Kit.”

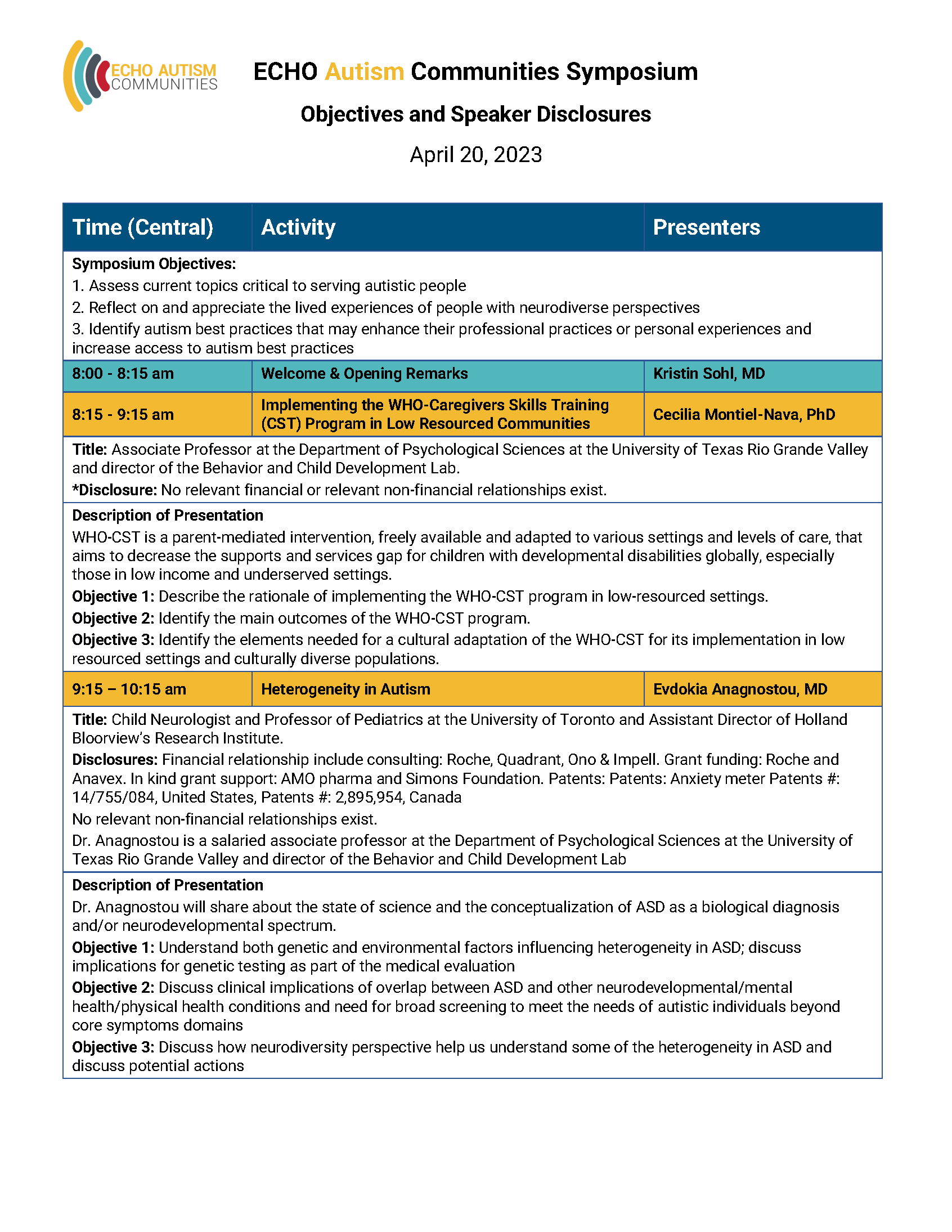

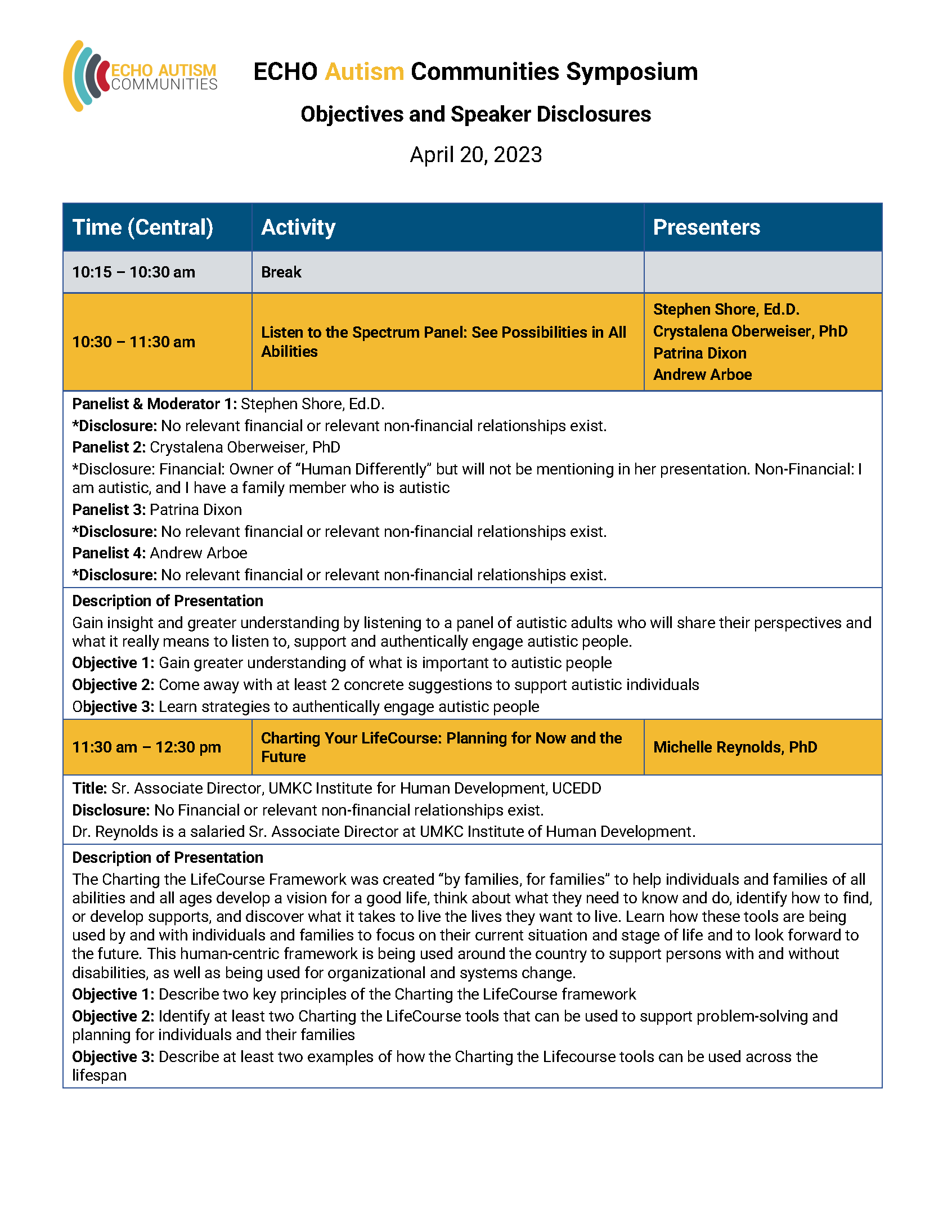

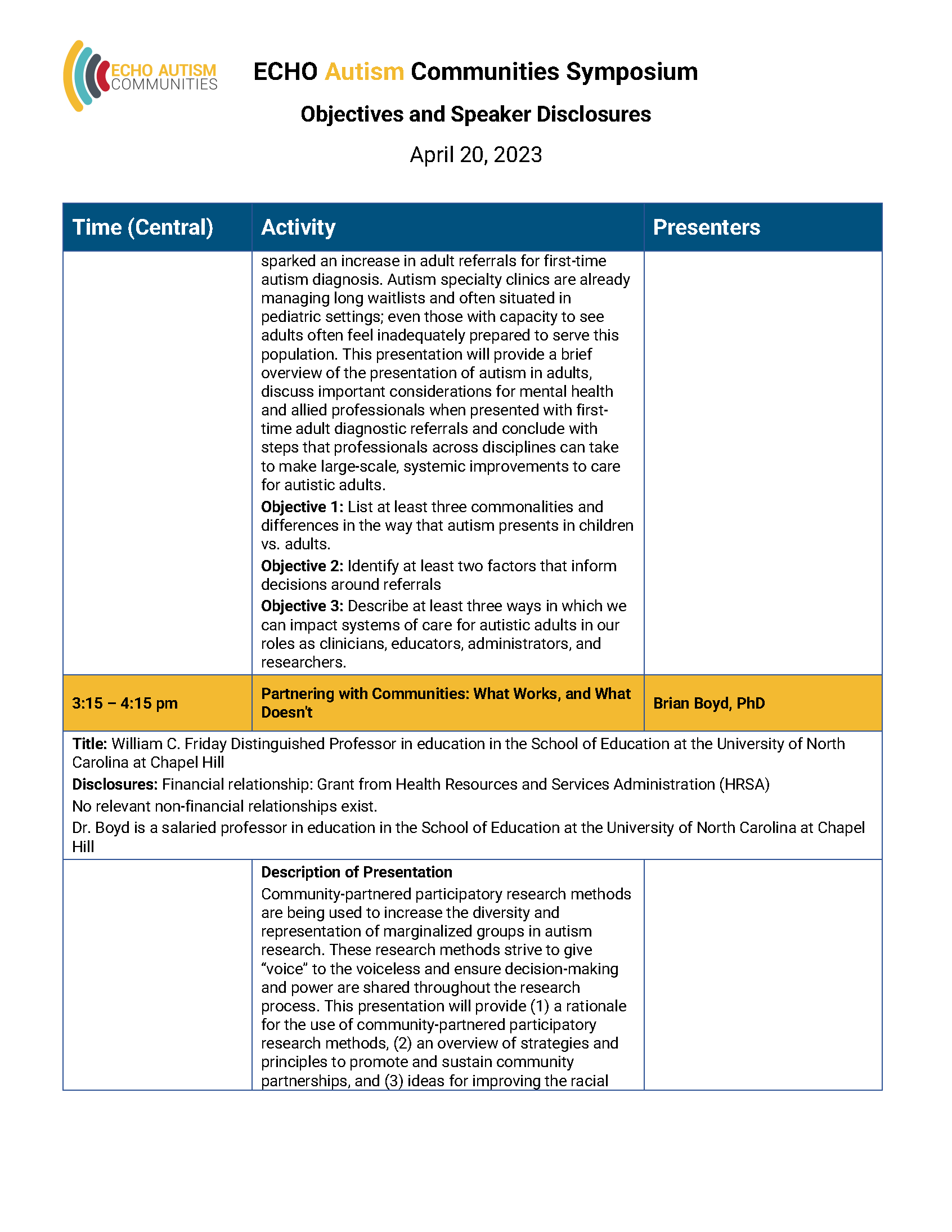

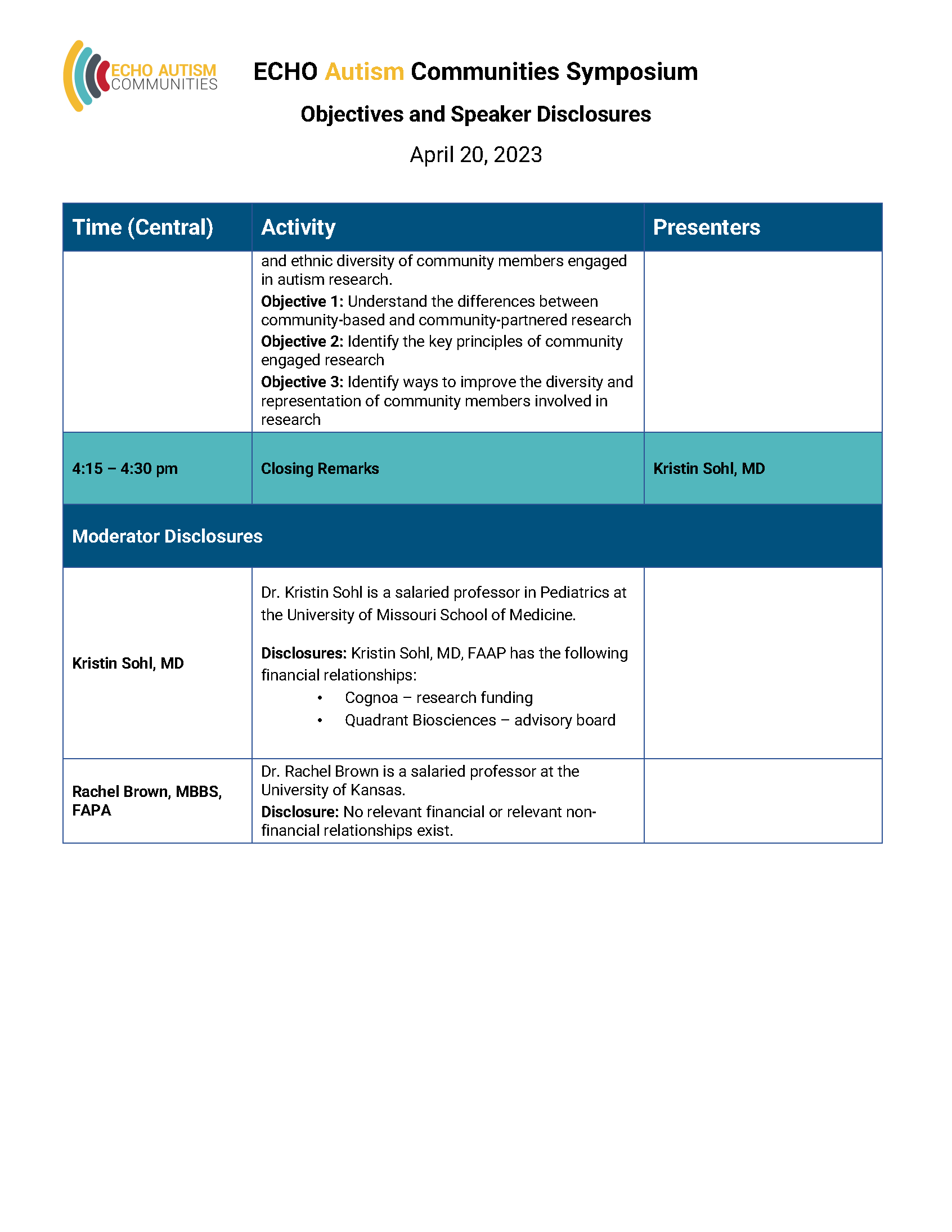

Join our community of providers today! You’re invited to our 2021 Symposium where we will address many important topics for healthcare providers, family advocates, and autistic people.

3 Comments

amanda

I love this! Living with undiagnosed autism is so hard when doctors don’t know what to look for and assume the symptoms are related to other things instead.